Volume 2 in the series Jung and the Epic of Transformation by Paul Bishop – Goethe’s “Faust” as a Text of Transformation – was released by Chiron Publications on October 1, 2025. This follows Volume 1, Wolfram von Eschenbach’s “Parzival” and the Grail as Transformation, released on May 27, 2024 and discussed in Episode 135. Professor Bishop returned to Speaking of Jung to discuss the book in Episode 152.

From the publisher:

For Goethe, his Faust was his “main business” (Hauptgeschäft), an opus magnum or divinum within the framework of which his whole life was so enacted. Or so believed C.G. Jung, who described himself as “haunted by the same dream,” as “launched upon a single enterprise” which was his “main business,” and someone in whom Faust had “struck a chord and pierced through” in a way he could not but regard as “personal.”

In Goethe’s “Faust” as a Text of Transformation, Paul Bishop considers the significance for Jung of this iconic work of German literature which embraces the periods of Sturm und Drang, Weimar Classicism, and Romanticism, and constitutes a major work in the German epic of transformation. In Parts One and Two of this dramatic poem (or poetic drama), Faust undergoes a series of transformations — as do those readers who, as Jung did, open themselves up to the transformational power of Goethe’s work.

This is the second volume in a series of books, examining key texts in German literature and thought that were, in Jung’s own estimation or by scholarly consent, highly influential on his thinking. The project of Jung and the Epic of Transformation consists of four titles, sequentially arranged to explore great works from a Jungian perspective and in turn to highlight their importance for interpreting The Red Book.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

List of Abbreviations

Editions of translations cited

“Faust” editions and commentaries

Works on Goethean life (in chronological order)

Works on Goethean aesthetics (in chronological order)

Jungian/alchemical readings of “Faust” (in chronological order)

Audiovisual recommendations

Acknowledgments

Preface

Chapter 1 Goethe’s Faust, Part One

Chapter 2 Goethe’s Faust, Part Two

Chapter 3 Goethe’s Faust in Jung’s Works [A]: Faust in Jung’s Autobiographical and Early Works

Chapter 4 Goethe’s Faust in Jung’s Works [B]: Faust in Jung’s Later Works of the Thirties, Forties, and Fifties

Bibliography

BOOK EXCERPT

From Chapter 1: “Goethe’s Faust, Part 1,” pages 12–18:

In Chapter 5 of Aion, Jung returned to the problem of the Antichrist and described it as a “hard nut to crack” for anyone who had a positive attitude toward Christianity (CW 9/ii §77). As late as the Book of Job, he observes, the Devil was “still one of God’s sons and on familiar terms with Yahweh,” referring for further discussion of this topic to the study by one of his followers, Rivkah Schärf Kluger (1907-1987), titled “The Figure of Satan in the Old Testament” (1953).¹⁰ It was only with the rise of Christianity, Jung noted, that the Devil attained his “true stature” as “the adversary of Christ, and hence of God” (§77). Yet Jung made clear that he was approaching the problem not theologically, but psychologically: Beside the “sublime and spotless” dogmatic figure of Christ, everything else “turns dark” (§77). In fact, this very one-sided perfection is said to demand “a psychic complement to restore the balance” (§77). And this “inevitable opposition” is said to have led to the doctrine (espoused, for instance, by the Gnostic sect known as the Bogomils) that there were in fact two sons of God, Jesus and an elder son called Satanaël (§77). Seen in this light, the coming of the Antichrist is “not just a prophetic prediction,” but rather “an inexorable #psychological law” — a law whose existence, even if not known to the author of the Epistles attributed to John, nevertheless brought him “a sure knowledge of the impending enantiodromia” (§77). In Jung’s view, there was a clear correlation between “every intensified differentiation of the Christ-image” and its “corresponding accentuation of its #unconscious complement,” a dynamic that brought about an ever-increasing tension between “above and below” (§77).

According to Jung, it is thus “in accordance with psychological law” (and not through the “obscure workings of chance”) that the “Christian disposition […] leads inevitably to a reversal of its spirit” (CW 9/i §78). This clash between, on the one hand, “the ideal of spirituality striving for the heights” and, on the other, “the materialistic earth-bound passion to conquer matter and master the world” (§77) — or, in Jung’s words elsewhere, “the Scylla of the renunciation of the world and the Charybdis of its acceptance” (PU §141; cf. CW 5 §121) — emerged in the Renaissance, that is, in the age of Faust, and is reflected in the architecture of the time: in the shift from the vertical, Gothic style to a horizontal perspective (voyages of discovery, exploration of the world and of nature) (CW 9/ii §78). Following on the Renaissance came the Enlightenment and the French Revolution, paving the way to our own “antichristian” time — or “end of time.” Thus, with the coming of Christ, those “opposites” that had hitherto been latent now became manifest; and, alluding to the words of Nietzsche’s Zarathustra, “But it is the same with man as with the tree. / The more he seeketh to rise into the height and light, the more vigorously do his roots struggle earthward, downward, into the dark and deep — into the evil” (Z I 8), Jung concludes that “the double meaning of this movement lies in the nature of the pendulum”: Christ is “without spot, but right at the beginning of his career” — namely, in his temptation in the desert — there occurs “the encounter with Satan, the Adversary, who represents the counterpole of that tremendous tension in the world psyche which Christ’s advent signified” (§78).

In Jung’s eyes, Christ is “our nearest analogy of the self” (CW 9/i §79). And yet it is in some ways an imperfect analogy, for although such attributes as consubstantiality with the Father, coeternity, filiation, parthenogenesis, crucifixion, being a lamb sacrificed between opposites, being One divided into Many, etc., are said to mark Christ out as an “embodiment of the self,” he nevertheless corresponds to “only one half of the archetype,” the other half of which appears as the Antichrist, the manifestation of the “dark aspect” of the self. Hence both are “Christian symbols,” which tells us the same thing as we are told by the image of the Savior crucified between the two thieves: namely, that “the progressive development and differentiation of consciousness leads to an ever more menacing awareness of the conflict” — i.e., of the opposites — “and involves nothing less than a crucifixion of the ego, its agonizing suspension between irreconcilable opposites” (§79). On this point, Jung quotes no less an authority than Origen: “It was proper, moreover, that the one of these extremes, and the best of the two, should be styled the Son of God, on account of His pre-eminence; and the other, who is diametrically opposite, be termed the son of the wicked demon, and of Satan, and of the devil” (Contra Celsum, Book 6, §45). And later in The Red Book, the crucifixion of the self becomes one of the great symbols in that work (RB, 197-198 and 388-389).

Thus, on Jung’s account the figure of Christ, as the Christian “image of the self,” is in an important respect fundamentally lacking, for it “lacks the shadow that properly belongs to it” (and this is Jung’s quarrel with the theological doctrine of the summum bonum) (CW 9/i §79-§80). In Memories, Dreams, Reflections, Jung describes Job as “a kind of prefiguration of Christ,” the link between the two figures being “the idea of suffering” (MDR, 243). Just as Christ was the “suffering servant” of God, so too was Job, and in the case of Christ the cause of his suffering is said to be the sins of the world: But who is really responsible for these sins? “In the final analysis,” it is argued, the responsibility rests with God, for He “created the world and its sins, […] and therefore became Christ in order to suffer the fate of humanity” (242). In Aion, Jung refers to “the bright and dark side” of the divine image, to the notion of the “wrath of God,” to the commandment to “fear God,” and to the petition in the Lord’s Prayer (recently revised by Pope Francis), “And lead us not into temptation” (or “Do not let us fall into temptation”) (243). Here lies the link between Jung’s thought and the Book of Job — and its “ambivalent God-image,” for Job “expects that God will, in a sense, stand by him against God,” and in this expression (“with God … against God”) we have “a picture of God’s tragic contradictoriness” (243). Yet here, too, lies a link to Goethe’s Faust, and to the wager struck between the Lord and Mephistopheles in the “Prologue in Heaven”; to Mephistopheles as the shadow-side of Faust himself; and to the frankly post-Christian notion of redemption in the work, according to which Faust, for all the suffering he has caused — especially to Gretchen in Part One and to Philemon and Baucis in Part Two — is, in the end, redeemed.

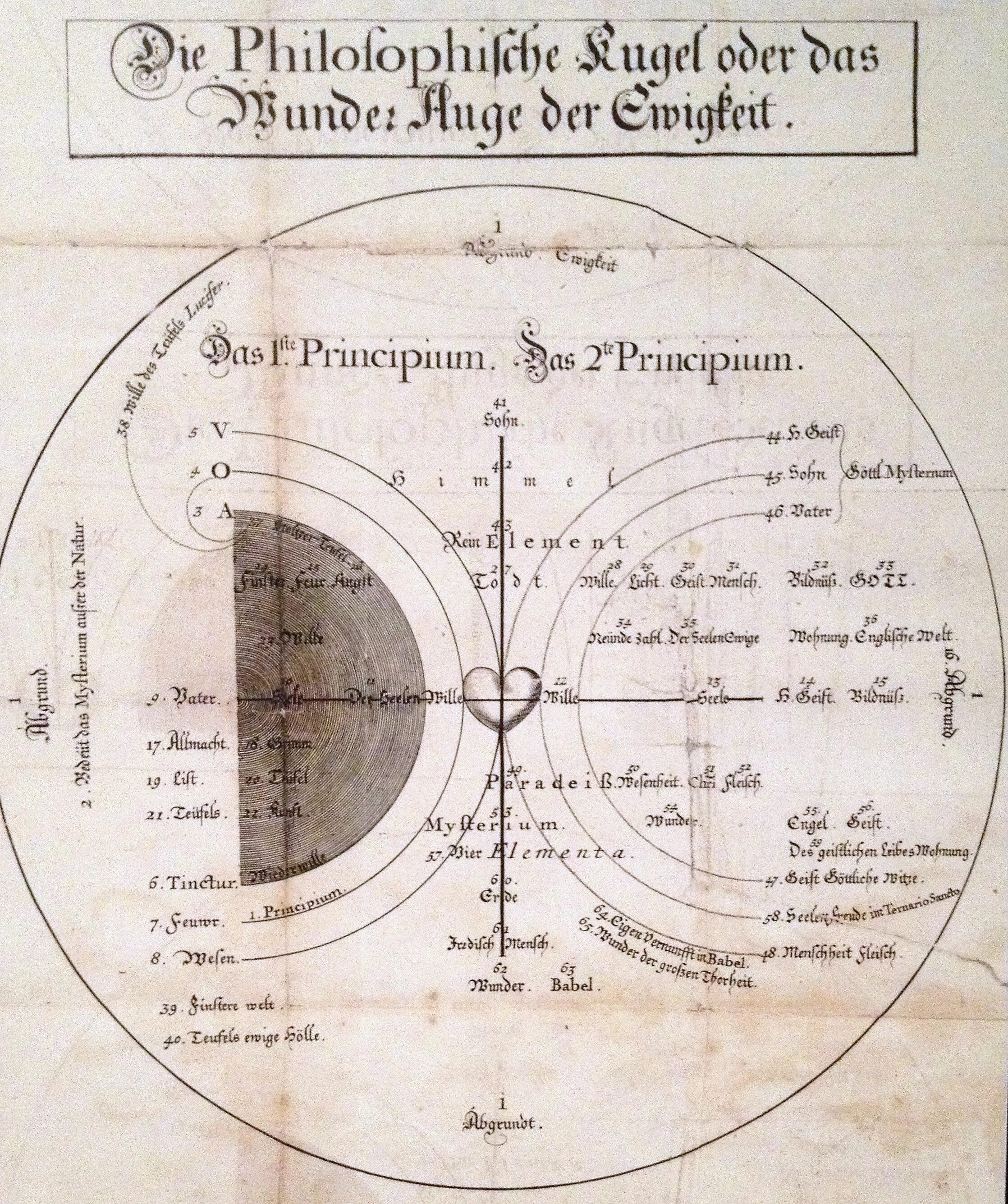

Figure 1. Böhme’s mandala. Image in the public domain.

This theme of the tragic contradictoriness is taken up, as Jung points out in Memories, Dreams, Reflections, in 1952 in Answer to Job (MDR, 243). In this work, which evidently constitutes a response to the biblical book, Jung applies the Gnostic model of fissure and emanation to what he calls the “Christian myth of salvation.”¹¹ As the Creator is whole, so is His creature — His son — whole, but within that wholeness a splitting ensued, and a realm of light and a realm of darkness emerged (MDR, 365). On Jung’s account, this development had been prefigured in the sixth century B.C.E. in the experience described in the Book of Job and in the third or second centuries B.C.E. in the apocryphal Book of Enoch, part of which (the so-called Book of Parables) belongs to immediate pre-Christian times. In Christianity, this metaphysical split had come to the fore, with the result that Satan, previously part of the immediate entourage of Yahweh, now turned into His diametrical opposite (MDR, 365). Not surprisingly, the view emerged at the beginning of the 11th century that it was not God, but the Devil, who had created the world — as the medieval Cathars are said to have believed (CW 9/ii §225-§226). This view is said to have sounded the keynote for the second Christian millennium (i.e., the second half of the Christian aeon); and the essentially paradoxical nature of the God-image is captured by the “visionary genius” of Jakob Böhme (1575-1624) in his mandala found in his XL Questions concerning the Soule (1620). In the English translation of this mandala, titled “The Philosophical Globe, or Eye of the Wonders of Eternity,” an outer circle contains the quaternity of Father, Holy Ghost, Sonne, and Earth, while the inner circle is divided into two semicircles standing back-to-back rather than closing (MDR, 366; CW 9/i §534, Fig. 1).

If, as Jung had argued in Aion, the appearance of Christ had coincided with the beginning of a new aeon, the age of the Fishes, the constellation under which the next aeon would stand is Aquarius, coinciding with the time when the complexio oppositorum of the God-image enters into humankind — not as unity but as conflict, as the dark half of the image (as represented in Böhme’s diagram) comes into opposition with the conventional Christian view that “God is Light” (MDR, 366) — a key idea in the New Testament, reflected in the First Letter of John, “God is light, and in him there is no darkness” (1 John 1:5), and a central theme in Wolfram’s Parzival, where Trevrizent tells Parzival in Book 9 how Plato and the Sibyl had foretold the redemption to come, and that Parzival must repent of his sins — “For He is a Light all-lightening, and never His faith doth cease” (§465, l. 19-28 and §466, ll. 1-4; vol. 1, pp. 268) (MDR, 248 and 366).

In Memories, Dreams, Reflections, Jung says that this process was taking place in his own time; and, if so, it must be taking place a fortiori in our own. One might even call our own age the Faustian age, inasmuch as the theological framework of Goethe’s drama apparently encompasses a shift from the traditional Judeo-Christian view of the opening “Prologue in Heaven” to the mysterious Eternal Feminine of the concluding scene in Part Two. At the center of Faust (with its “Prologue in Heaven”) and at the center of Answer to Job alike stands the notion of transformation: the transformation of Faust from his service to God in an obscure or confused way (verworren dient) into clarity (in die Klarheit) (ll. 308-309) in the former, and the transformation of the God-image and of humankind in the latter — “the future birth of the divine child” or “the metaphysical process […] known to the psychology of the unconscious as the individuation process” (CW 11 §755), the transformation of God into humankind and of humankind into God. The former ends with the Eternal Feminine who zieht uns heran (“draws us onward and upward”), the latter with an evocation of “the One who dwells within […], whose form has no knowable boundaries, who encompasses [us] on all sides, fathomless as the abysms of the earth and vast as the sky” (CW 11 §758).

¹⁰ See Rivkah Schärf, “Die Gestalt des Satans im Alten Testament,” in C.G. Jung, Symbolik des Geistes (Zurich: Rascher, 1953), pp. 151-319; and Rivkah Schärf Kluger, Satan in the Old Testament, trans. Hildegard Nagel (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1967).

¹¹ For further discussion, see Paul Bishop, Jung’s “Answer to Job”: A Commentary (Hove and New York: Brunner-Routledge, 2002).

Excerpted from Chapter 1: “Goethe’s Faust, Part 1” in Jung and the Epic of Transformation, Volume 2: Goethe’s “Faust” as a Text of Transformation, by Paul Bishop, Ph.D.

VOLUME 1

📙 Jung and the Epic of Transformation, Volume 1: Wolfram von Eschenbach’s “Parzival” and the Grail as Transformation Chiron Publications, 2024

🗣️ Speaking of Jung, Ep. 135 Professor Paul Bishop on the first volume in his series, Jung and the Epic of Transformation, recorded on January 29, 2025