From the publisher: The release of The Red Book generated enormous interest in Jung’s visual works and allowed scholars to engage with the legacy of Jung’s creativity. The essays collected here present previously unpublished artistic work and address a remarkably broad spectrum of artistic accomplishment, both independently and within the context of The Red Book, itself widely represented. Tracing the evolution of Jung’s visual efforts from early childhood to adult life while illuminating the close relation of Jung’s lived experience to his scientific and creative endeavors, The Art of C.G. Jung offers a diverse exhibition of Jung’s engagement with visual art as maker, collector, and analyst. Contains 254 illustrations.

IMAGES FROM THE UNCONSCIOUS

An Introduction to the Visual Works of C.G. Jung

Carl Gustav Jung’s first publication, in 1902, was his dissertation in psychiatry for Zürich University’s medical school. It was the beginning of a lifetime of literary work that stretched beyond psychiatry and psychotherapy to religious studies and cultural history, encompassing more than two dozen widely translated books, with the release of further unpublished material still ongoing. Jung’s international reputation as a successful writer and skilled lecturer is irrefutable, yet, for decades, few suspected the vital role that visual art played in his oeuvre.

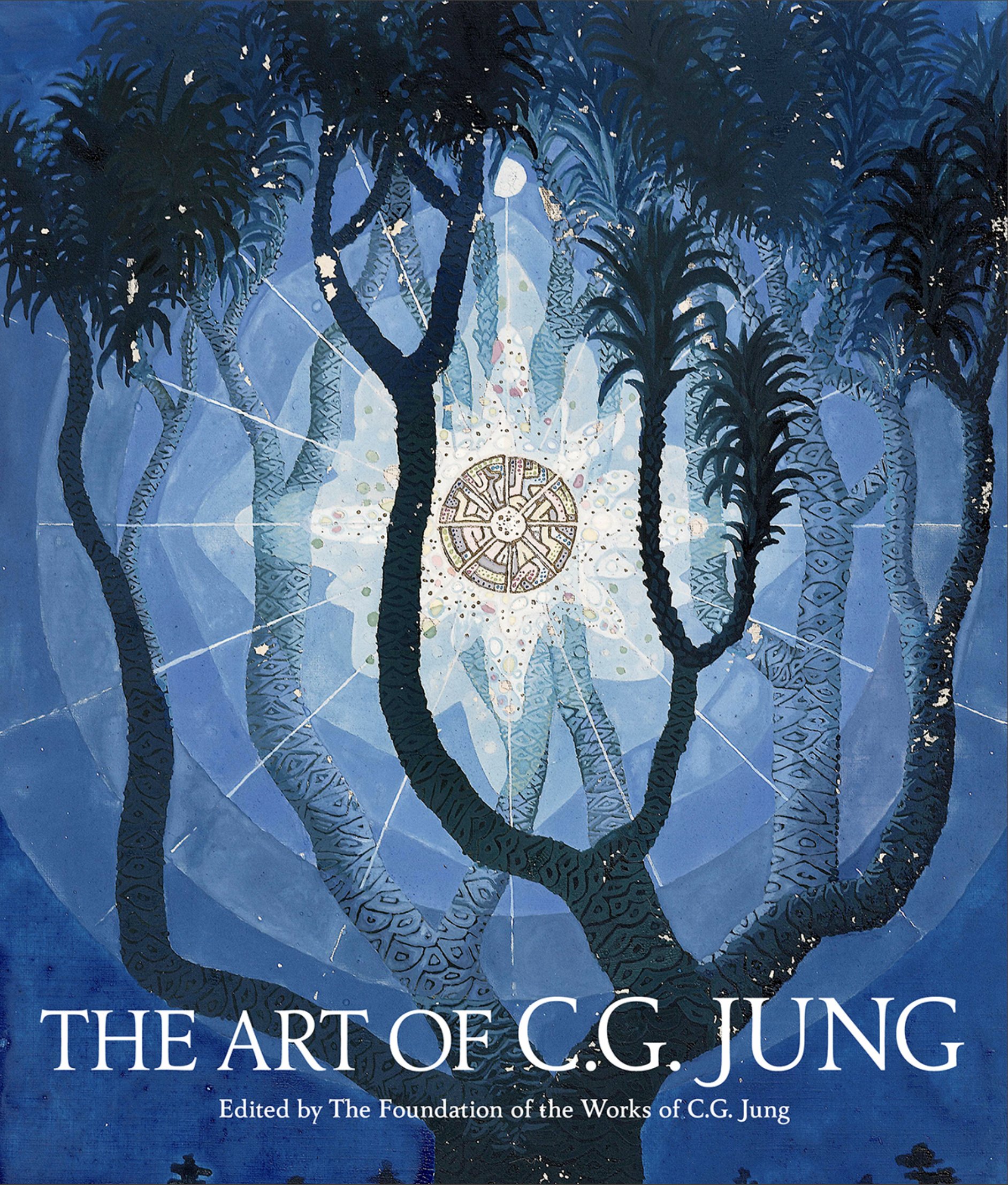

In 1929, together with the German theologian and Sinologist Richard Wilhelm, Jung published a book on a mysterious ancient Chinese text. Published in English in 1931 as The Secret of the Golden Flower, it contained Wilhelm’s translation of the treatise and a psychological commentary on it by Jung, ‘Examples of European Mandalas,’ which was intended to provide the Western reader access to Chinese thought. Jung explained that the linguistic images in the Chinese text were to be understood as symbols for psychic processes with which he was familiar from his practice. According to Jung, Europeans would spontaneously create similar images for psychic processes, especially in the form of circles, flowers, crosses or wheels, so-called mandalas. In his view, ‘by these analogies, an entrance is opened a way to the inner chambers of the Eastern mind.’

Examples of European mandalas illustrate the commentary, Jung noting: ‘I have made a choice of ten pictures from among an infinite variety of European mandalas, and they ought, as a whole, to illustrate clearly the parallelism between Eastern philosophy and the unconscious mental processes in the West.’ He described the characteristics of the individual mandalas in short captions, without naming their makers or identifying himself as the creator of three of them.

In 1947, Jung contracted with the Bollingen Foundation in New York to publish his writings in a collected edition: The New Edition, today known as The Collected Works. The agreement defined the contents of the edition as ‘works and writings […] written or made by the author,’ but the attached schedule did not mention visual works.

A volume of essays published in 1950 contained, under the title ‘Concerning Mandala Symbolism,’ an expanded version of the ‘Examples of European Mandalas’ with extended and more specific commentaries. Jung as the creator of four of the mandalas was still not acknowledged, the works being attributed to an anonymous ‘Middle-Aged Man.’

In 1955, to accompany Jung’s text ‘Mandalas’ and a picture of an ancient Tibetan mandala, the Swiss periodical Du published a ‘Mandala of a modern man’ entitled Systema Mundi Totius (Structure of the whole world). Again, the reader could only suspect that Jung was the creator of this mandala, as well as the author of the elaborate commentary. In Volume 9/I of the Collected Works, published in 1959, the Systema Mundi Totius appears as the frontispiece, again without revealing the identity of the mysterious ‘modern man’ credited as its maker.

Among Jung’s acquaintances, however, it was no secret that he sometimes produced visual works. In the garden of his home in Küsnacht stood a sculpture of a bearded man with many arms. Furthermore, Jung had given some of his close friends paintings or wooden figures. He even showed some of them The Red Book – a thick folio volume bound in red leather containing Jung’s own calligraphic texts and intensely colorful images – and in the 1950s, at his retreat at the upper end of Lake Zürich, the Tower at Bollingen, he could be seen carving stone. Yet Jung died in 1961 without having published any of his visual works under his own name.

One year later, Memories, Dreams, Reflections appeared, which for the first time allowed a view of Jung as a private person. Among other insights, he described in some detail the making of some of his mandalas, paintings, and sculptures, and – in the chapter ‘Confrontation with the Unconscious’ – the origins of The Red Book. However, with the exception of one page from The Red Book and the Stone at Bollingen (a stone cube Jung covered with symbols and inscriptions), no visual works were reproduced in Memories. Nonetheless, this open account of his creative engagement with the arts attracted great interest.

Ulrich Hoerni

Foundation of the Works of C.G. Jung

From the preface to The Art of C.G. Jung. Edited by The Foundation of the Works of C.G. Jung: Ulrich Hoerni (Jung’s grandson), Thomas Fischer, and Bettina Kaufmann. Translated from the German by Paul David Young and Christopher John Murray. Published by W.W. Norton & Company, 2017.